Paths Crossed: Magdalena Wosinska

From baring it all to bearing it all, the acclaimed photographer talks skate parks and storytelling, mothering and moving into a new era of softness.

I was first introduced to the force and photographer that is Magdalena Wosinska through her images and essays. Sat at my desk in Berlin, copyediting the stories behind her ongoing nude series, the Magdalena Experience, I recognized a fellow adventurer, fiercely free as she crossed rivers and trails in search of herself and the shot.

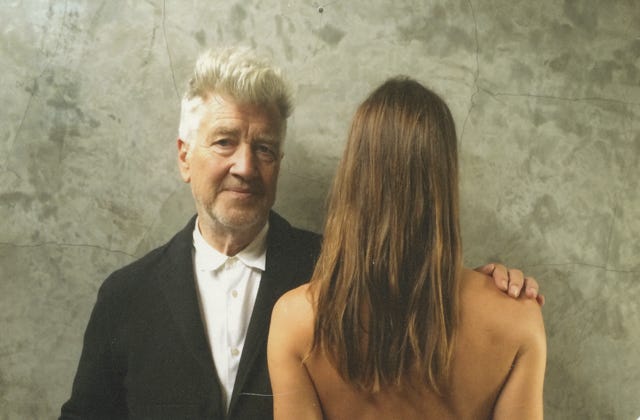

Since that time, I’ve followed along with what is an impressive career and vast body of work both commercial and editorial, discovering our many intersecting scenes and communities via music, arts, surf, and skate. Countless artists have looked into her lens—Kim Gordon, David Lynch, Nicole Kidman, Joaquin Phoenix, to name but a few. From the New York Times to the New Yorker, Harley Davidson to the North Face, her collaborations are far reaching.

But beyond her impressive career, it is through one of her personal projects of the last years that I found myself deeply struck. Magdalena lost her mom in 2021, and chronicled the journey and unbreakable bond across caregiving and grief to such a stark, honest, and stunning degree. She unmasked much of what we hide from in this culture when it comes to death, revealing what is natural, tender, and full of love. I lost my mom in 2020 and deeply connected to her expressions of the experience.

Magdalena and I finally met in person this past fall at a launch for her book, a time capsule into the skate culture of the 90s as seen through her then 14-year-old lens—a Polish immigrant new to Arizona who frequented the skate parks and found a common language in the counterculture. When she grabbed my hand and ushered me through the bar with such effortless affection and familiarity, it should not have surprised me. She’s a woman’s woman, open and authentic while full of attitude and edge, undoubtedly having the backs of all of her people. Here, we dig into it all.

First off, how are you doing? [This interview was conducted on the heels of election day, which holds up on the heels of inauguration.]

I'm not giving into the fear. It was obvious to me that this was going happen. So I'm going to make the most of it, surround myself with community and family and friends and make sure that we don't feel divided, because that's the fear.

That makes sense to me—as an artist, you can see through the macro lens too.

I think it's also a Polish thing. When we find a problem, we always find a solution to the problem. So the solution is to just not let this be a problem.

How would you define the heart of Polish culture, what is that?

I think there's certainly a post-war, communist mentality involved. So while it may be operating from places of scarcity or fear, it allows you to be more frugal, resilient, and a very hard worker. A lot of people that I know who are Polish are like machines—they’re reliable people that get shit done. And I think that's something that was embedded into my mother and father, and that naturally passed down to me and my sisters. So you just don't take shit for granted. Everything is an honor. Taking photos is an honor. Going to a restaurant, having someone serve you food is an honor. Someone washing your car for you if you can afford it is an honor.

You came here from Poland when you were young. I’m curious to hear your perspective on the immigrant experience. It’s certainly on my mind in the current moment—the U.S. being a different place than the one my Eastern European great-grandparents arrived to in search of safety and freedom.

I don’t know if the freedoms were as freeing as people think they are, even in the 90s. Because with freedom of expression, you have to learn how to step into yourself to have that. You can have that in any culture, wherever you grow up. I definitely didn't feel free when I came here because I felt extremely outcasted, like I didn't belong. I had a weird name. Kids aren't very welcoming when you're new and different. Sure, maybe I looked a lot more like people that lived here, but that still wasn't easy. So I don't know if there's a sense of different limitations of freedom; you have to kind of figure that out for yourself. If I’d stayed at home, maybe I would have still had the same ways to express myself, because now Warsaw is booming. It's like a mini New York City; it's so fucking cool. My dad is back there now. After my mom died, I told him to go.

So let me step back for a moment and ask you how you would introduce yourself?

I’m a storyteller.

And photography is your main medium?

Yes. I would love to transition into more filmmaking. Not transition—I would love to do both. But it's such a big world that I'm still a bit fearful of because I don't know enough. But sometimes not knowing a lot keeps you just ignorant enough that you don't have too much fear. The more I learn, the more scared I get. So maybe I should just do.

After arriving in Arizona in 1991, you got into photography hanging out as a teen in the skate parks, is that right? You’ve talked about not speaking English, but observing the common language of skaters and punks as an outsider.

Yeah, I started to shoot photos of skateboarders when I was 14, and always documented the things that were around me.

And home base for you now is California?

Los Angeles, yes—I've been here for 20 years.

Is it home? Or do you feel like home and belonging is different places at different times?

In my soul and in my spirit I’m Polish. In my physical existence, it's LA. Where my mind goes to is definitely still with a mentality of how I was raised in our Polish culture, because it was embedded into our home, even though we moved to America. But I've been in LA for half of my life now. So this is definitely home and where my community is. If something crazy happened, and I needed to live in another place or country, I'd be super open to it, as long as I still have a sense of community there. Whereas even up until a year ago, I wasn’t open to that.

I have a permanent EU visa now after living on and off in Berlin since 2011. Always good to have options.

That’s amazing. I travel a lot and I'm always pulled to European culture and people, because I feel like I can relate more to people that are a little more blunt and forward. Whereas I notice that in America, everyone always says, How are you? And it’s like, I'm good. How are you? That's bullshit. You're not good. Can you tell me the truth? But at the same time, when I spend a lot of time there, I do miss it here, because there's such vast, abundant, beautiful places here to find so many different things with different cultures in nature.

I’ve had interesting debates with Berliners about those pleasantries you note, and how they are conflated with all Americans being fake. I didn’t realize all at once that living abroad was life-changing, but of course the nuances seep in after years of exposure to different ways of being.

For me, if you're a passionate person in Poland, that's just the fire inside you. You're a woman of fire and it's attractive and sexy. Here, people call you intense, and they automatically quote intensity as a negative thing. In Europe, women and men are treated differently when they're older. Women are looked at as elegant and graceful and iconic into their fifties and sixties. I's really hard for this society and this culture to look at women that way.

I agree with that, and the social scenes in Berlin do feel more mixed up, across generations. It was years back in Berlin that I was first introduced to your work. I was assigned to copyedited your essays for a book on your nude series. No need to rehash why the project got pulled at the eleventh hour, with you maintaining creative control and your integrity! But can you tell me more about the heart of that series? I know it can be misunderstood, though you have been doing it way before Instagram culture.

It’s a series that’s probably going to go on forever because it's been going on for 20+ years. It's about me trying to find my femininity and freedom. When we moved to America, we didn't have money. We moved from a communist country with two suitcases and like 300 bucks in the bank—my mom and dad and three daughters. So we didn't get to experience the American culture as rolling into something cool. I remember looking at magazines when I was younger, and the people on the covers were supermodels wearing Chanel outfits. And I thought, I want to be a photographer—I want to shoot things that are cool and could potentially get into magazines. But I don't have the right clothes. I can't afford these clothes. If I wear my clothes, everyone will know I'm poor, and I don't want people to know I'm poor. But if I take my clothes off, nobody will know that I'm poor. So I just got naked.

Wow, so that's how it started.

You can't tell what social class I come from. You can't tell the year, the era, what kind of music I'm into, if I'm a preppy or a fucking hipster or a raver. And I was like, You can't judge me. But what happens in America? Everyone judges you for being naked because they oversexualize it. I get a lot of shit for that account. The art world didn’t always take me seriously because they're like, Oh, the chick with the naked butts on Instagram. And the commercial world, or threatened male creative directors, didn’t want to hire a photographer who also does a series of nudes. If I was spread eagle in a leather thong, it's different—those women are making so much money on OnlyFans doing it. And good—do what you need to do. But this is my artistic practice, I’m literally climbing mountains, getting chased by wild horses, and crossing freezing-cold rivers with frostbite on my toes to get the shot.

And the commercial work—name a brand, you’ve worked with them—did that evolve out of years of art and editorial?

It comes from always photographing my environment. Luckily, a lot of that translates into commercial work, which I'm so grateful for because I love doing that stuff. I love working in community, in teams, having my friends be on set with me. And I can take whatever income I get from that and put it back into making books. It's hard work. You have to constantly hustle but I’m grateful I can do it.

You have a new book out of your skate images called Fulfill the Dream. I took note at that Q&A that it was born of all these negatives sitting under your bed for 30 years, that it felt like time to give them to the world, that you no longer needed them. I liked the anecdote that the magazines you looked up to in the 90s like Thrasher are now full circle writing up the book you did on your own terms.

Yeah, it was really nice to put this book together. I made three books before this. I was 24 when I did my first, a collection of music photos. Then I made a book about an ongoing nude series I do. The third is a book about love called Leftovers of Love that I never made public. That was super heavy. And then I made this book, and it feels like the one I needed to put out for the world to understand the foundation of where I come from—a prequel of sorts so that by the time the book about my mom comes out, people understand. The book about my mom is finished, and already was before the skate book.

Can you discuss the book about your mom’s life?

I found a box of negatives in the attic of our house when my mom was passing away, when we moved from our family home in Arizona. I developed all the negatives, and there were photos of her entire childhood and her meeting my dad, and then the youth of our family and my sisters. I got to see my mom in a light that I've never seen her before—not a mother, but a teenager, a young woman, a professional. And at that point, my mom had been partially paralyzed and sick for 16 years, so I’d forgotten what she was like. The beginning of the book starts with the images of her life and black-and-white photos that my dad took when they started their relationship. And then it slowly transitions into me taking her pictures when she was already sick, and the dance as the role reversal of child and mother happens—how she changed my diapers and how I now changed her diapers. She watched me take my first breath; I watched her take her last breath.

I was looking forward to talking with you about this relationship with your mom and the journey you took with her as you shepherded her through death. I had just gone through the same thing—hugging my mom as she took her last breath—and was still very much processing it all as I was witnessing you going through it via your stark, beautiful documentation in images and captions on Instagram.

When did your mother die?

It was 2020, and I’d just turned 40.

Yeah, my mom died in 2021 as I neared 40.

I remember I was compelled to write you at the time, we exchanged a couple of messages. I felt you so deeply, and recognized a similar vulnerability in self-expression and sharing what is an inevitable rite of passage that is so often hidden from view.

Thank you. Yeah, there were a lot of things that my mom still needed to tell the world and let out of her system before she passed, and I happened to be the person by her bedside that she told those things to. Learning about her allowed me to learn a lot about myself and where I come from and why I do certain things. We just became closer—she started allowing me to take photos of her. After she was partially paralyzed, she wasn't this bombshell walking into a room anymore. She didn't want to be seen. And I slowly gained her trust; she was able to let me see her and take her picture. And eventually she started to perform for me—pose and dress up in all her pink outfits. She always wore pink so she could be seen and be loud in a room because her vocal cords were paralyzed, her voice wouldn't carry the attention she needed anymore.

I love that she became part of your creative process, and you hers. One of the photos you took of her, sitting in the bath with her, was published on the front page of the New York Times. How did that come about?

It was kind of a coincidence in that one of the creative directors there reached out asking to use this photo for a cover after I posted it on Instagram. I said of course, but told them that I would love for my mom to be a published writer in America before she passes, because she used to be a writer in Poland—the cultural difference in the immigration and her status didn't allow her to do that here. So my mom did get to be published before she passed away, she wrote a paragraph that accompanied it. I had to ask her if she was okay with signing a model release to be on the cover of the New York Times. What's the New York Times? she asked me. One of the biggest publications in the world, I told her. And then she asked, Why would they want two naked women in a bathtub bathing each other on the cover? Because it's about tenderness, I replied.

The way you expressed your emotions with such truth on your page struck me, and it mirrored my own experiences and expressions as I lost my mom. I have so many pictures of my tears during that time, and of her, of a lot of things. I think I turned my camera on myself as a witness, because I was so alone in it, let alone as the pandemic broke out. I processed her mind and then body deteriorating as I’d drive home every night to her empty house, after all the advocacy, hospitals, hospices, care facilities, with nowhere to put it and a need to reach out.

Me too with the photos of my tears. When people say it takes courage to share something, I was like, Oh my god, I was so alone in this. I needed the support from strangers on a fucking app called Instagram, because I was sure as hell not getting it from my family. Sometimes I felt like strangers understood my true essence more than really close people in my life, the people there by default. But how lucky that we are able to feel like we shared something in this way.

I think people get so uncomfortable with vulnerability and therefore attack it. For me, it's not really something I’d know how to opt out of. And if I could help one other person feel seen, it’s worth someone else shaming me for it. I wish I’d seen that back then though—that I was standing in my power and strength through something very major. I wish I could have owned what I needed versus having allowed that shame in. But it’s all a process.

As an artist, the youngest of the family, the youngest to lose my mother, and the only one without a husband and kids, this is how it felt right for me to connect. I was also going through an insane breakup at the same time my mother is dying. As an artist, this is how I was coping with the pain, whereas those close to me were scientists, people who could compartmentalize. And now those close to me love it—they're grateful I took the photos. But that was their way of coping with their grief too. There was anger towards me sharing it, and I'm not upset about it—anymore—but they just didn't understand what it meant to me. I think it took time for it to sink in—and maybe the validation of strangers telling them how beautiful I was and what this was.

When someone messaged me and thanked me for my openness, knowing they’d have to experience and go through parts of this in the future, it meant a lot. But when people called it brave, I don’t know that that holds—though I think of you as brave. And fierce in your capacity to have gone all in in being your mom’s caregiver as this time in life arrived.

Yeah, it's weird for me that people wouldn't do it. So many people reached out to me that it was so special, what I did. But in a way, it almost made me sad. Maybe it’s a disconnect, where men feel uncomfortable about their older mom that needs a bath. It’s like dude, you came out of her vagina, stop tripping. American culture sexualizes or makes things gross or weird. This is the most natural thing to do. Bathe your old mom. Bathe your old dad.

It's so humbling while so very hard. Of course a couple times I was like, I'm done, I'm out, I can't do this. But I just needed a minute to act out, I knew I didn’t mean it.

Yeah, that was our ego being like, Fuck, I'm exhausted. The amount of times I had to fight her to get her in a bath, and there's shit or blood everywhere. It was insane. Also, everyone thinks that if we take care of our mothers, we're super close, but that's not necessarily the case. I came very quickly after my sister died. My sister died when she was six. My mom never could say my sister's name. We couldn't wear black in the house. There couldn't be candles in the house because it reminded her of the funeral. And then I came, and so my mom was grieving, and I was there to supposedly be the band-aid for the family, the fix-it kid. Talk about having anxious attachment from that. But it’s all very real. And she did take care of me the best she knew how. So I will do whatever the fuck I need to to make sure that you're good too. And you probably felt that way too.

My mom’s psychiatric illness and advocating for care in that way had its own set of things to contend with and have to see and unwind. But she also absolutely did the best that she could, yes. And she loved fiercely. Three years on, what is your relationship with your mom?

She isn't a physical form for me anymore. She became a form that was even closer and more present in a way, because she wasn't suffering, she didn't have limitations of paralysis or disease. But at the same time, I had to learn in the gnarliest way to take care of myself and self-soothe. I had to be able to mother myself and be my best friend, and I struggle with that so much. But there are these moments where I'm like, fuck, I've always had this with me, and in me; I just completely forget to tap into it, because I tap into the fear and anxiety around it, because I can feel other people's energy.

I also relate to parts of the journey you discuss that entail unlearning, cycle breaking, seeing ourselves for who we are—all that work that doesn’t just disappear after one’s death when you’re enmeshed.

Yes. Coming from a place of so much trauma that you might have, and your mother, and I might have come, and my mother, how lucky are we that we have a voice in this lifetime as their daughters to break the chain in the cycle of this bullshit. People will not value you unless you value yourself. It's hard. It's so much fucking work. I never knew life was only going to get this much harder as I got older. But it is so worth it to wake up out of the pits of despair and pain, to pull yourself out of the fucking mud and be like, but I have my heart, and I know its value.

What are you most proud of right now?

Where I am at emotionally.

You've referred to the girl in the leather jacket trying to be tough, trying to be taken seriously in the skate park. And now the girl taking the armor off and stepping into her femininity and vulnerability. Would you say that’s the journey?

Totally. Softness. Bring it on.

Of Note: As an artist who is part of the Los Angeles community, Magdalena is generously offering to photograph families who lost their photo albums in the fire. Reach out: magdalena@magdaphotography.com

Thank you, Rachel. This was a gorgeous, authentic piece. Congrats. Your work makes me proud of you and inspired to keep leaping into the risk of writing. Much love and respect

What a beautiful and power-filled conversation and set of images! So needed in this moment. Thanks to both of you for your candor.